Had slain UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson hired an armed guard through Protector — a new private security app billed as “Uber with guns” ― he might still be alive, the company posited in a video reenactment of the killing.

In that reenactment, the “Protector,” identified by HuffPost as Los Angeles Police Department officer James Zourek, describes how he looks for “pre-incident indicators” to detect threats. These, according to Zourek, include “inappropriate clothing for the environment or weather conditions, unusual gait or lack of arm-swinging, indicating they’re concealing a weapon, and frequent checking of pockets or waistband.”

Advertisement

The video shows Zourek shooting the suspect as he approaches Thompson, “eliminating the threat,” as Zourek puts it.

Protector promises to “empower individuals” with “access to elite protection.” It delivers military expertise “from the frontlines to your front door,” according to its promotional materials.

But what happens if a Protector gets it wrong? What if the sweatshirt-clad man swinging his arms insufficiently as he walks toward the customer isn’t a threat, but a loved one who runs cold and has stiff joints? Tucked into the fine print of Protector’s terms of use agreement is language waiving the company of any responsibility if, for example, your armed guard accidentally shoots your dad.

Advertisement

Protector, the company claims, is “act[s] solely as a technology platform facilitating connections between users and independent security professionals” and “cannot guarantee specific security outcomes or the performance of any individual agent.” The armed guards available through Protector “operate as third-party providers, and we do not control, direct, or assume liability for their actions,” the Terms of Use agreement states.

screenshot from Protector’s Terms of Use

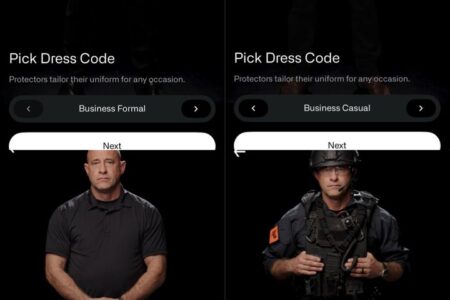

The app was launched in February by former Facebook product designer Nick Sarath. It allows users to select the number of cars in their “motorcade” and the number of so-called Protectors, who can be outfitted in Business Formal (a jacket and a tie), Business Casual (no tie), Tactical Casual (performance polo shirt and cargo pants), and Operator (SWAT cosplay), although the latter is currently unavailable.

Advertisement

Bookings start at $100 per hour with a five-hour minimum and require a $129 annual membership, according to the company. (When HuffPost opened the app to make a reservation with one car and a single Protector, the cost was $1,500.)

After Protector initially launched in Los Angeles and New York City, HuffPost asked regulators in both places whether the company had obtained permits to operate as a rideshare or black car business. The California Public Utilities Commission confirmed that Protector did not have a Transportation Network Company permit and that the agency was investigating whether one was required. By Thursday, Protector’s services were pulled from Los Angeles. Nikolaj Leszczynski, an account manager at the PR firm hired by Protector, confirmed on Friday that “L.A. is down” but did not respond to multiple questions about the reason.

New York City’s Tax & Limousine Commission told HuffPost that Protector was a private security company and, therefore, not part of the agency’s regulatory jurisdiction.

Advertisement

Last year, a similar armed rideshare service called BlackWolf quietly suspended operations in Phoenix and Scottsdale after Axios reported that it failed to acquire the Arizona state permit required for rideshare companies.

Every Protector is a current or former member of the military or law enforcement, according to the company. The company’s LinkedIn features flashy videos with close-up interviews of Protectors listing their military and law enforcement credentials, with photos of them heavily armed in warzones scattered throughout.

“This app is an attempt to gamify warfare,” Mohammad Tajsar, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California, said in an interview. “It’s the perfect Silicon Valley gimmick. Take a fake problem — rising crime — offer a fake solution that you only find in video games, dress up your own squad of goons and roll it out to a crowd of internet-brained pseudo wealthy people who want this kind of dystopian future.”

Advertisement

When I first reached out to the company in February, Leszczynski initially indicated a willingness to schedule an interview with Sarath, the company’s founder, and a ridealong so I could get “the Protector experience.” But Leszczynski later backtracked and said that Sarath “and his Protectors are extremely swamped” and could only respond to questions over email.

The company then declined to respond to a detailed list of questions about its policies, vetting and training practices, and the past conduct of its contractors. Instead, the company said in an emailed statement, “We are simply offering a new innovative option in the traditional personal security space — immediate access to the protection you want without the usual red tape, hassle, and confusion.”

Although the app refers to the drivers by their first names, HuffPost identified at least four Protectors who, as of March 7, were also working as Los Angeles Police Department officers, according to the agency: Zourek, Royce Burroughs, Nicholas Cho and Andrew Rea, none of whom responded to requests for comment. (SWNS reported that Zourek retired in January; neither Zourek nor Protectors answered an email seeking clarification.)

Advertisement

LAPD’s employee manual allows officers to hold secondary employment after the department reviews the proposed job and determines it is not “incompatible” with LAPD employment. The manual states that LAPD officers cannot take on secondary jobs that involve using the “badge, uniform, prestige or influence” of their position for private gain or advantage. LAPD did not respond to an email asking if officers advertising their status as LAPD officers to promote their private security work violated the department’s policies.

LAPD declined to disclose whether Zourek, Cho, Rea or Burroughs have disciplinary records with the department, so HuffPost filed public records requests under California’s Right To Know Act. Although that records request is still pending, publicly available court records, as well as one of the Protectors’ public statements, provide some information about the conduct of the police officers hired by Protector.

Screenshot from Protector app

Advertisement

Zourek, who is prominently featured in Protectors’ promotional materials, has been with LAPD since 1997. A self-described “knuckle dragger,” Zourek has also worked as a Marine Corps Scout Sniper in Iraq, a federal prison guard and a firearms instructor. In December 2023, while head of LAPD’s union, Zourek gave an hour-long interview on a podcast called “The IA Guy” about his treatment by the police department’s internal affairs division, which investigates allegations of misconduct.

“One hundred percent of the job” of an internal affairs investigator should be protecting cops, Zourek said, stating that it’s a “detriment” to the police department for an officer to “feel like you’ve been run through the ringer.”

Early on in his career, Zourek was given a 22-day suspension “for unnecessarily extending a lawful detention,” he said on the podcast. One of the lessons he learned from that incident was the importance of being honest during the internal investigation — up to a point. “Look, if you got a body buried in the backyard, roll the dice, don’t tell them about it,” he said.

Advertisement

In 2004, Zourek put an unarmed man suspected of removing property from a stolen vehicle in a carotid restraint, or a chokehold, causing the suspect to lose consciousness, court records show.

“The LAPD ridiculously, they consider a carotid restraint, or a chokehold, they consider it a lethal use of force,” Zourek said on the podcast, relaying the incident. “If that’s true, then every night in jiu jitsu, I’m committing attempted homicide.”

LAPD suspended the use of carotid restraints in 2020 after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. California lawmakers banned the practice later that year.

Advertisement

Zourek took the case to LAPD’s disciplinary appeal board, which found him guilty and recommended a five-day suspension. Zourek filed a writ of mandate in Los Angeles County Superior Court, arguing that his conduct was reasonable based on the information he had at the time, and that his punishment was inconsistent with LAPD’s past practice. In 2007, a judge granted Zourek’s petition and directed LAPD to rescind the suspension and reimburse Zourek for lost wages, with interest.

Zourek has “zero lessons learned” from that incident, he said on the podcast. “I will do it every day, all day, I don’t care about the five-day suspension,” he said of the chokehold. “I’ll do it tonight if I go out there. Because I’m 100% in the right.”

After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, Zourek wrote in a group text, “I haven’t seen the democrats this mad since we freed their slaves,” LAPD watchdog William Gude reported on X. Zourek was initially suspended for the text, but was later cleared of wrongdoing by the disciplinary board.

Advertisement

HuffPost asked Protector if the company has a use of force policy, offers deescalation training to its Protectors, has a mechanism to review allegations of unnecessary force and if it reviews LAPD disciplinary records before hiring officers. In response, Protector said that with “rigorous vetting and extensive training,” their team members follow all laws. “They adhere to the highest standards of professionalism, safety, and integrity, with extensive expertise in de-escalation tactics to ensure peace of mind for all.”

Another LAPD officer who works with Protector, Royce Burroughs, is currently a named defendant in a civil suit brought by a woman who alleges that he was part of a team of LAPD officers who, while responding to a hostage situation, blew up a door and wall of her apartment while she was inside, stormed through the hole in her wall, and pointed guns at her while she frantically tried to keep her kittens from running away. The woman went on to suffer from symptoms of traumatic brain injury, as well as anxiety, depression, back pain and a sensitivity to loud noises, she said in the complaint.

Before Protector launched, Burroughs and fellow LAPD officer/Protector Nicholas Cho operated their own private security company called Delta Special Operations Corp, where they advertised being active members of LAPD’s SWAT Team, offering private services starting at $150 per hour.

Advertisement

A name search of Cho and Rea in LA’s Superior Court database did not produce any court cases with allegations of misconduct.

It’s not clear who Protector is intended for. Ultra-wealthy people with an ongoing use for private security will simply hire their own security detail. The service is too expensive for most people and it’s hard to imagine many scenarios in which someone would have a one-time use for private security that doesn’t involve committing a crime.

The company’s terms of use prohibit specific behavior, including hate speech, harassment, stalking, defamation and child sexual exploitation, but does not include a blanket ban on unlawful activity, like buying drugs. It’s also not clear how the company would prevent its services from being used to carry out the activity it purports to ban. What’s to stop an abusive man from hiring a Protector to lurk around his ex-girlfriend? Asked how it would prevent such use of its services, Protector said, “Protecting lives is a grave responsibility, and it’s one we take very seriously. Any attempt to exploit our services in any way will result in immediate suspension and account termination.”

Advertisement

Protector plans to soon launch a companion app called Patrol, which would allow residents of neighborhoods in Los Angeles to crowdfund professional neighborhood security patrol. Like Protector, Patrol provides private citizens with the ability to hire current law enforcement officials for their personal security whims.

The presence of apps like Protector and Patrol “create the fear the apps claim to respond to,” Tajsar, the ACLU lawyer, said. “If the apps exist, it creates the sense that there must be crime, and we must need private security,” he said, noting that crime levels are, in fact, declining.

“It is clearly designed to appeal to rich people’s anxieties, which is basically what policing in America is,” Tajsar said.

Advertisement

“It’s basically class warfare right in front of us.”